A/B Testing for Scammers

I don’t know whether to feel happy or sad that scammers are A/B testing poorly. I recently received two emails, that were obviously part of an experiment done poorly. They’re shown below, but a few notes for a potential future scammer.

Test Subjects

It isn’t strictly wrong to use the same user for both arms of the A/B test (although then you’d need to test whether the treatment order matters), but for something like this, it is generally better to focus on a two-sample test. Anecdotally, I don’t think people would respond to one and not the other purely as a function of the messaging. Therefore, you should only send each user one treatment within a given time period. While you’d sacrifice some statistical power using a two-sample test rather than a paired test, you’d probably have a more accurate measurement overall.

Treatments

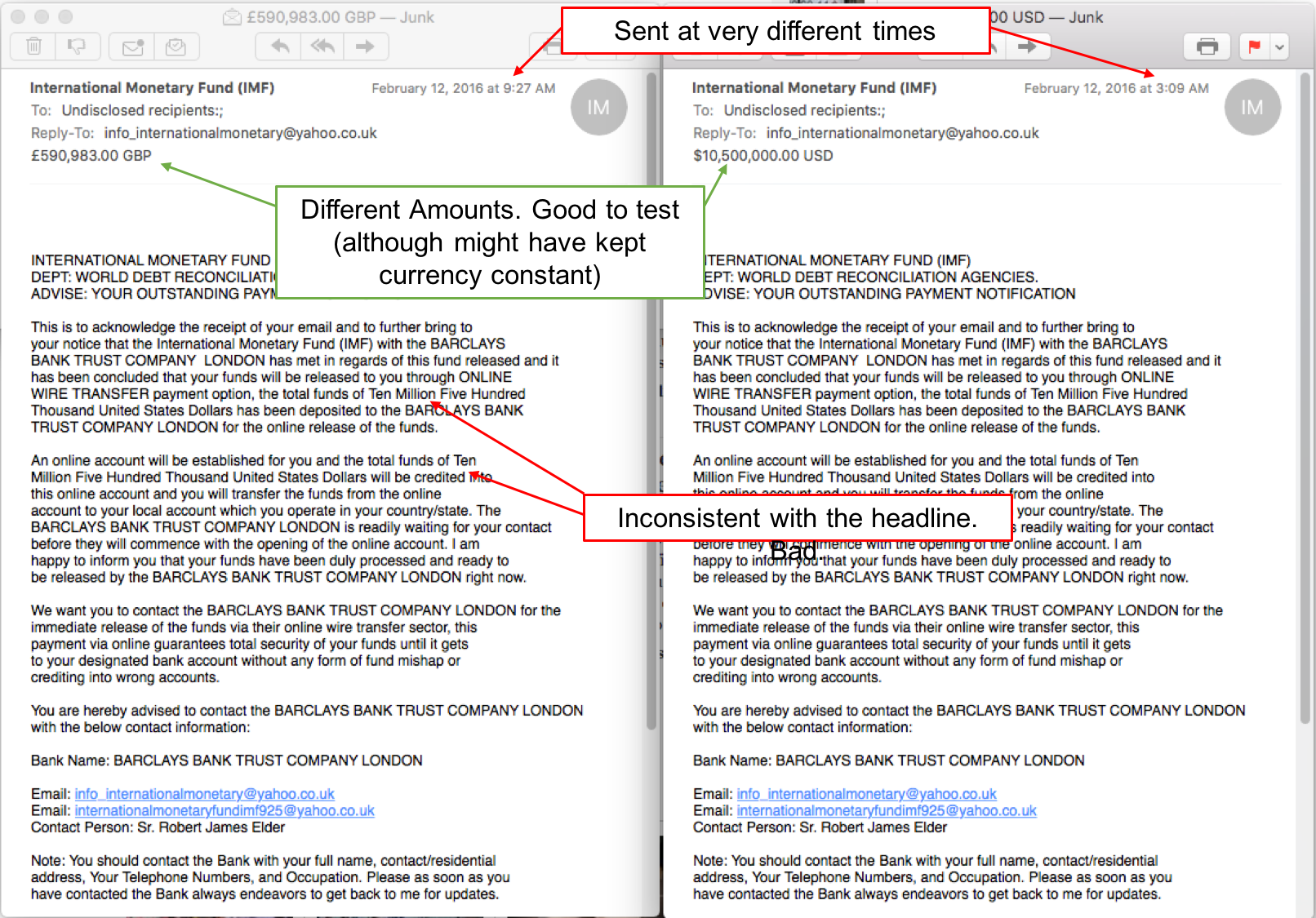

Here the scammers changed the amounts in the title, which is a great component to experiment on; they’re testing whether odd numbers are more likely to generate the target behavior than even numbers. Buzzfeed has found something similar with their listicles.

My primary concern with their treatments are that the amounts and currencies differ by quite a bit. It is one thing to test whether someone reacts better/worse to an even/unusual amount, but it is another to test whether the sweet spot is ~$10M or ~$1M, and whether they’d react differently to USD vs GBP.

Another issue related to the treatment: they used different numbers in the body of the text. This seems like a simple oversight, but means that any response they detect may be a function of the inconsistent text, thus potentially nullifying any results from this experiment.

Dependent Variable

A little more difficult to notice, but here the scammers would have a difficult time detecting whether there was any response. I think they should have used a subtly different email address for each of the messages, that way they could keep track of responses, although maybe they’re assuming the user will actually just click ‘reply’ and add the email addresses in themselves.

Confounding Variables

Finally, these emails were sent at pretty different times. While it is possible that they’re controlling for this (through randomization of when the emails are sent), there’s quite a bit of evidence that the timing of emails matters. By sending one email in mid-morning and the other in the middle of the night (in my time zone, at least), this confounding variable may cause erroneous results.

Conclusion

While the use of a randomized control trial is laudable, its misuse can misinform and even lead to the wrong conclusions. As more non-specialists use RCTs (the apocalypse must be near – they’re even teaching these things to MBAs nowadays), these errors are more likely to occur. Look to a statistician or a reliable online resource to make sure you don’t make these simple mistakes.

Notes

Clearly this post is meant as a satire. I am not a lawyer and don’t condone trying to scam anyone. I do not take responsibility for the consequences of this post. I mostly meant to help people understand a little about what makes A/B tests useful and useless.